Considering future scientific discoveries, the geneticist J.B.S. Haldane wrote “the Universe is not only queerer than we suppose, but queerer than we can suppose.” But that statement applies as much to the past as the future. As paleontologists continue to chip away at the fossil record they are continuing to find organisms that no one ever could have ever expected. And if life on Earth can be so strange, what might these creatures mean for different evolutionary paths taken on other planets? As you go about inventing fauna for your own sci-fi worlds, here are some mind-bending critters to keep in mind.

Opabinia

To borrow a line from Nigel Tufnel, “No one knows who they were, or what they were doing.” With five eyes perched on short stalks, wings of segmented exoskeleton, and a pincher-tipped schnozzle hanging out in front, Opabinia was among the oddest of Cambrian oddballs. The 505 million year old fossil is so strange, in fact, that paleontologists initially couldn’t figure out where it fit in the tree of life. Today it seems most likely that little Opabinia was most closely related to the forerunners of arthropods, even if it looks like it looks like it would be more at home in the seas of Titan.

Uperocrinus

At first glance, a crinoid might look like a feathery plant with fuzzy arms radiating from an anchoring stalk. But they are actually animals—relatives of sea urchins and starfish—that are some of the greatest survivors of all time. Aside from the species that populate the world’s oceans, crinoids have been filtering food from the seas for over 480 million years. Some of the strangest of all lived in the distant past. Uperocrinus nashvillae, a species dating back to over 323 million years ago, looked like invertebrate impressions of a morning star—knobbly, club-like, and adorned with spikes to keep hungry snails away. Not a crinoid you’d want to cross.

Thylacoleo

Thylacoleo was the closest thing to the Australian myth of the drop bear. Belonging to the same group of marsupials as kangaroos and koalas, this leopard-sized carnivore sheared through flesh rather than leaves—piercing prey with pointed incisors and slicing muscle with cheek teeth that resemble meat cleavers. And with strong forearms and retractable claws, this deadly mammal likely capable of climbing trees to get the jump of the unwary Ice Age mammals it lived alongside. For an otherworldly predator, you could do a lot worse than Thylacoleo.

Therizinosaurus

Dinosaurs did weird pretty well, but there was hardly a species stranger than Therizinosaurus. Roughly the size of a Tyrannosaurus, this 70 million year old theropod was a long-necked, tubby, feather-covered herbivore equipped with insane, Freddy Krueger-style claws. What the dinosaur used those claws for is unclear—perhaps spearing fish, stripping bark, or slapping around tyrannosaurs that got too close. Regardless, out ideas about what a dinosaur is would surely have been shaped differently if Therizinosaurus and its kin had been discovered earlier in the history of paleontology.

Pterodaustro

Avatar’s “Ikran” weren’t doing anything that pterosaurs hadn’t done better. The flying reptiles—not dinosaurs, but rather close cousins—soared through the Mesozoic skies on wings of skin supported by ridiculously-elongated fourth fingers. That made pterosaurs odd enough, but the 105 million year old Pterodaustro was especially strange. This pterosaur had a long, slightly-upturned mouth with bristly filaments sticking up from the lower jaw. Along with stomach stones that Pterodaustro used to grind food in its stomach, this suggests that the pterosaur fed by filtering tiny invertebrates out of freshwater lakes. Pterodaustro—the terror of plankton.

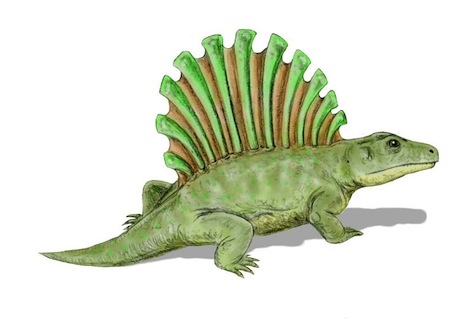

Platyhystrix

How do you make an amphibian look flashy? Put a sail on it! After all, that technique worked for b-movie makers who wanted to turn lizard and alligators into faux-dinosaurs, but the 300 million year old amphibian Platyhystrix had the style down all the way in the Permian. The question is why the stumpy, 3-foot-long amphibian had evolved such impressive ornamentation. Regulating body temperature is the traditional hypothesis, but showing off for members of its own species can’t be ruled out, either.

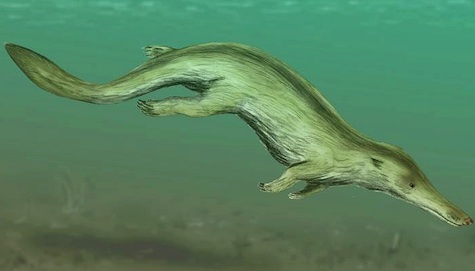

Kutchicetus

The evolutionary transition from land to water—repeated over and over again through time—does weird things to vertebrates. A prime example is Kutchicetus, a 47 million year old fossil whale that looked more like a long-snouted otter. The mammal probably swam like an otter, as well—undulating its spine up and down to propel itself after fish and other small prey. While not a direct ancestor of today’s cetaceans, Kutchicetus was nevertheless a sort of evolutionary experiment in whaleness as these mammals became ever-more suited to life in the water.

Erbenochile

Everyone loves trilobites. How could you not? The prolific arthropods had a good run during prehistory and have become fossil icons. And while they all adhered to the same basic body plan, some of these segmented invertebrates had some especially strange modifications. Erbenochile, a trilobite that crawled over the sea floor 385 million years ago, saw through dozens of lenses packed on tall, crescent-shaped towers that were its eyes. This arrangement was so effective that Erbenochile could see 360 degrees around, giving it a heads’ up on any predators that might swim by.

Helicoprion

For fishy weirdness, you can’t beat Helicoprion. For over a century paleontologists puzzled over whorls of teeth that seemed to belong to some kind of shark that swam seas all over the world over 250 million years ago, although where those spirals fit on the actual animal was hard to say. Researchers put them everywhere from the tail fin to the snout before experts arrived at the conclusion that the blade of teeth must have fit in the lower jaw. Finally, in 2013, paleontologists unveiled the true nature of Helicoprion—a snub-nosed ratfish that lacked teeth in the upper jaw and held that peculiar buzzsaw upright in the lower jaw. How Helicoprion used that peculiar weapon on the squishy cephalopods of its time is currently open to speculation.

Atopodentatus

Atopodentatus had zipper jaws. A 245 million year old marine reptile, Atopodentatus had a split, downward-curved upper lip lined with tiny, needle-like teeth. There’s no animal alive today with such a jaw, so how this marine reptile fed is a mystery, but the paleontologists who described the animal think that Atopodentatus might have grubbed through muddy sea bottoms to filter out crunchy little crustaceans. And if a creature so odd as Atopodentatus could go undiscovered for so long, who knows what else the fossil record has in store for us?

Brian Switek is the author of My Beloved Brontosaurus (newly out in paperback from Scientific American/Farrar, Straus and Giroux) and Written in Stone. He also writes the National Geographic blog Laelaps.